Teaching math in a different way

Recently on my Facebook news feed I found one article, which was rather interesting. "Teaching mathematics differently?" - ironical thought crossed my mind, while at the same time recalling some stand up comedians telling "wild" stories about the problem-based learning. It is truly funny to hear that children nowadays are forced to help the squirrel to count the nuts! Or to solve another default setup: "10 apples + 4 pears = 48 Litas, while 5 apples + 6 pears = 32 Litas, if so then how many Litas does a single apple or pear cost?" Why should anyone solve this problem in this way? Can't the client just look up the price tags? Or check his receipt?

The thoughts above are taken from, or at least inspired by, the article on The Spectator. Further in this text I will take up one interesting, in terms of the Physics of Risk, problem given in the aforementioned article, Also I will consider another similar problem, which was on my mind for a quite some time... So I'll start by giving Alice advice on Bob and I'll follow up by considering the so-called "Monty Hall" problem.

So, should Alice marry Bob?

So the problem stated in the article in The Spectator is as follows. Alice is dating Bob, whom she feels to be the best match for her so far (previously she was in two relationships). One day Bob asks Alice to marry him, but she isn't so sure about her answer. Since childhood Alice has dreamed to get married by her 36th birthday, while until that day going through 8 serious relationships. So should Alice accept Bob's proposal or should she stick to the "plan"?

The point here lies in the fact that any of 8 "planned" boyfriends has an equal probability to be the best match for Alice. Namely each of them has a 1/8 chance. Namely we known that Bob is the best of three, thus his chance is 3/8. Yet Alice expects to have 5 more boyfriends and the best one of them would have 5/8 chance to be the best, and thus better than Bob. Thus mathematicians would suggest Alice on rejecting Bob, because the probability to meet better guy than Bob is large.

The answer appears to be rather unnatural, but it is statistical correct. Why? It is so because Alice doesn't know any information on her future boyfriends, nor she does know the "fitness" of the remaining single males. Thus she can't objectively estimate Bob's fitness! She doesn't know how many of the other potential mates would be better than Bob. Therefore she can only rely on the previous experience and future dreams.

If you're not convinced by the simple solution, i.e. not relying on the heavy math, above you can follow a more complex mathematical path. Let us assume that the fitness of single males is distributed as \( p(x) \). If so then the fitness of the best male of N males will be distributed as:

\begin{equation} p_N^{max}(x) = C_N p(x) \Pi_{i=1}^{N-1}\int\limits_{0}^x p(x_i) \mathrm{d} x_i . \end{equation}

Here \( C_N \) is a normalization constant, which is kept to allow more options. Namely we can allow \( p(x) \) to have non-zero values outside the selected range of \( x \) (we restrict it in the region between 0 and 1). The formula follows directly from the self-imposed restrictions - we assume that the fitness of the supposedly best mate is \( x \) (which is selected at random from the \( p(x) \)), while the fitness of other N-1 candidates should be worst than \( x \) (thus the multiplication by N-1 of integrals).

Therefore the probability that best-of-3 mate will be better than the best-of-5 mate is given by:

\begin{equation} p_{3>5} = \int\limits_0^1 p_3^{max}(x_3)\int\limits_0^{x_3} p_5^{max}(x_5) \mathrm{d} x_5 \mathrm{d}x_3 . \end{equation}

Interestingly enough we obtain we same result for different \( p(x) \) - 3/8. Though this is not so unexpected (recall the "simple" solution above). The result might be generalized for different values of \( N_1 \) and \( N_2 \):

\begin{equation} p_{N_1>N_2} = \frac{N_1}{N_1+N_2} . \end{equation}

Thus every decent mathematician would suggest Alice to marry the next best boyfriend after Bob.

Note that while this problem to be more realistic, it is still far from the real life. In order for the suggested strategy to work the number of single should be infinitely large and Alice should pick her boyfriends purely at random. And even in such case only 5/8 of all "Alices" would make the correct decision. I'd highly doubt if that is smart enough for the decision of such importance.

Monty Hall problem

Let us now continue with a similar problem in which the use of statistical decision making appears to be more responsible. This problem is known as "Monty Hall" problem in honor of Monty Hall, long term host of "Let's make deal" (very popular show in the US, back in the 20th century).

The game is played as follows. At first the player choose one of the three doors. Behind two of them there are minor, or even humoristic, prizes (ex., goats), while behind the third door is a very good and expensive prize (ex., car). After the player makes his choice, the host opens one of the non-selected doors. It is worthwhile to mention that the host always opens the door, which hides a "goat". After doing so the host proposes a deal - he offers the player to trade his choice for whatever is behind the non-selected closed door! So what should the player do?

At the time there were a lot of arguments concerning the optimal player strategy. Some people claimed that there were no optimal strategy, because the options are equally probable, namely 50-50. This ought to be so, because the prize can be behind one door or another. Namely the choice is one of two. While the others made a correct notion that while the choice is one of the two, but the two options are not equally probable!

Why the options are not equally probable? Note that the only important choice is the first one! During the first choice you have a probability of 1/3 to select the right door and 2/3 to select the wrong door. The second choice can be simplified to the choice of whatever you believe you were right or wrong in your first choice. As the probability that you were wrong is twice as large as being right, you should opt to switch the door.

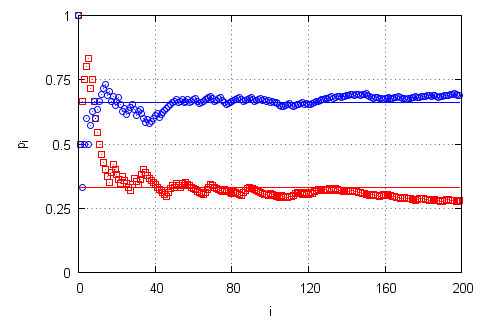

Fig 1.Evolution of the percentage of wins in the Monty Hall problem: switching strategy (blue circles) and staying strategy (red squares). Note that the percentage of wins converges to the expected results while the number of games grows to infinity.

Fig 1.Evolution of the percentage of wins in the Monty Hall problem: switching strategy (blue circles) and staying strategy (red squares). Note that the percentage of wins converges to the expected results while the number of games grows to infinity.Unfortunately this problem is so simple that the only explanation can be done is already outlined. If you still lack confidence in what was said, you can optionally try to do some numerical modeling or study our results (see Fig 1.). Note that you must do the "full" modeling - first let an agent choose a door, then open any door with a goat behind it and only then apply the selected strategy - to obtain correct results.

To conclude

I'd like to finalize this text by saying that the attractiveness of mathematics depends on the presentation. Yes, while some basics should not be neglected for the "eye candy", math should be taught in the most attractive manner. The same "requirement" should by applied for any subject taught at school, which quite far from the every day real life situations.

May be in this way it would be possible to avoid something in the spirit of the image below (taken from science.memebase.com; author: YUNOtele).

Fig 2.Real life math?

Fig 2.Real life math?