Can Lithuania's Economy Catch Up and Overtake Western Countries?

Can Lithuania catch up with and even overtake Western Europe? This question is provocative—but not without foundation. A recent study [1] showed that Lithuania's economic progress stands out among the countries of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). Yet can this growth pace enable it to reach the level of Malta and other Western economies? Using the same data and methodology, we compared the development of Malta and Spain to identify which factors determine successful convergence.

Malta's example demonstrates that even small and open economies can achieve remarkable progress and move toward the level of developed countries. Meanwhile, Spain's convergence has stalled, revealing limited prospects for faster growth. An analysis of these differences helps to assess the role played by foreign direct investment (FDI), price levels, and government debt dynamics.

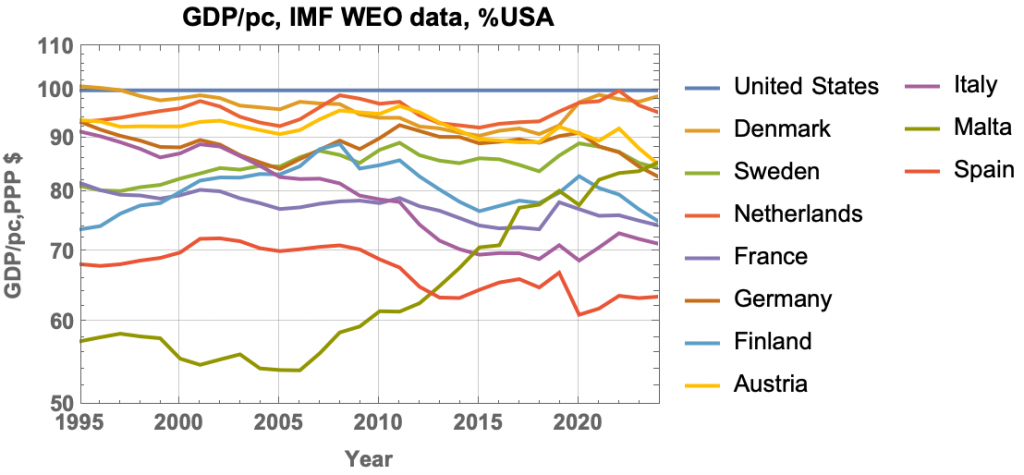

Fig. 1:Gross domestic product (GDP) per capita for Western countries, Europe, and the United States, calculated in Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) terms and normalized to the U.S. level.

Fig. 1:Gross domestic product (GDP) per capita for Western countries, Europe, and the United States, calculated in Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) terms and normalized to the U.S. level.The illustration shows the undeniable success of Malta, a small and open economy that, over a relatively short period, has caught up with and even surpassed several Western countries. During the same period, the older economies appear largely stagnant, moving almost synchronously with global economic and financial cycles. Malta's case appears inspiring and can serve as a practical model of economic policy—one that confirms the feasibility of not only catching up but also surpassing. Spain's chances of matching the more developed countries appear limited; yet, comparing its macroeconomic indicators with those of Malta helps reveal the main reasons for Malta's success.

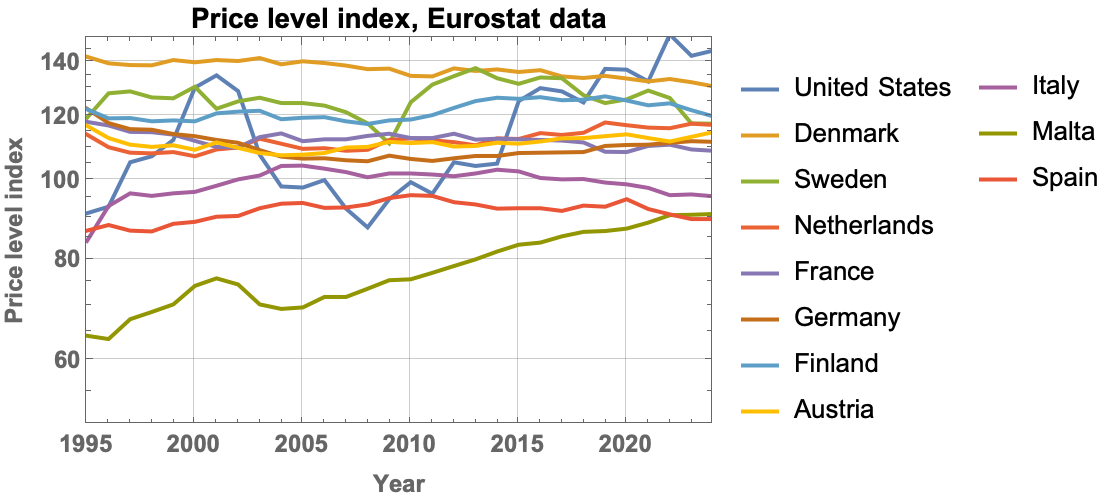

Figure 2 presents the changes in the price-level index (according to Eurostat) for the selected countries. As expected, Malta's economic growth has also been accompanied by a rise in prices, while fluctuations in U.S. price levels suggest that the dollar's exchange rate and monetary policy remain key sources of global economic volatility.

Fig. 2:Changes in the price-level index calculated by the PPP method.

Fig. 2:Changes in the price-level index calculated by the PPP method.A notable observation is that countries whose convergence with the U.S. has stagnated also exhibit stable price levels, with only minor fluctuations.

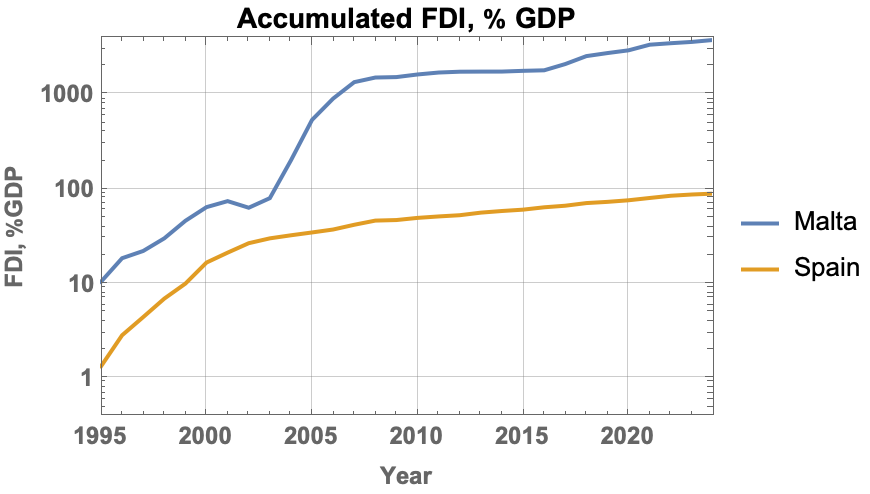

Data analysis shows that the economic growth of both CEE and Western and Southern European countries depends heavily on accumulated FDI. Therefore, Figure 3 shows the changes in Malta's and Spain's accumulated foreign direct investment over the analyzed period.

Fig. 3:Accumulated foreign direct investment in Malta and Spain.

Fig. 3:Accumulated foreign direct investment in Malta and Spain.The data clearly demonstrate that Malta's strong economic growth began precisely when major foreign investment projects were completed. This growth phase, which started around 2006, continues to this day and is one of the few pronounced positive trends among the mature democracies. Spain's FDI has also grown, but its pattern is typical for Western European economies.

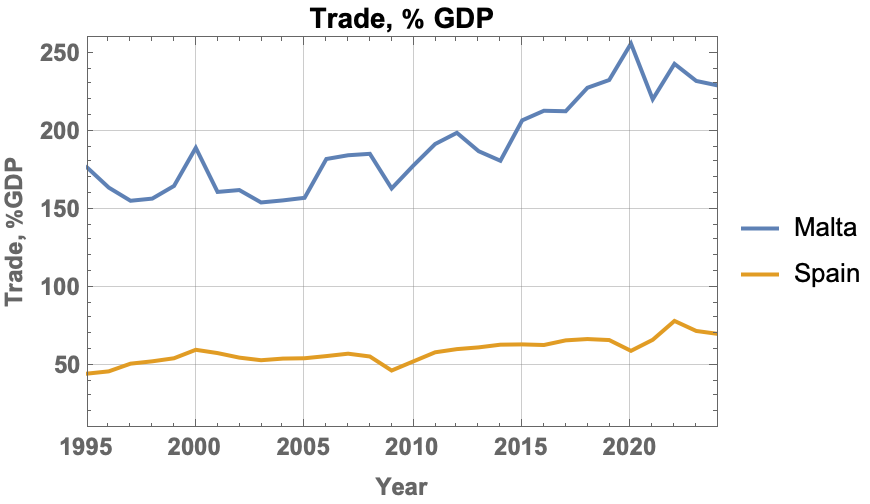

Foreign trade is another crucial factor, especially for small economies. Figure 4 shows that Malta's foreign trade expansion coincides with the surge in FDI. It is worth noting that the trade volumes of other countries also increase at rates similar to Spain's, while their absolute levels depend primarily on the size of each economy.

Fig. 4:Foreign trade of Malta and Spain during the analyzed period.

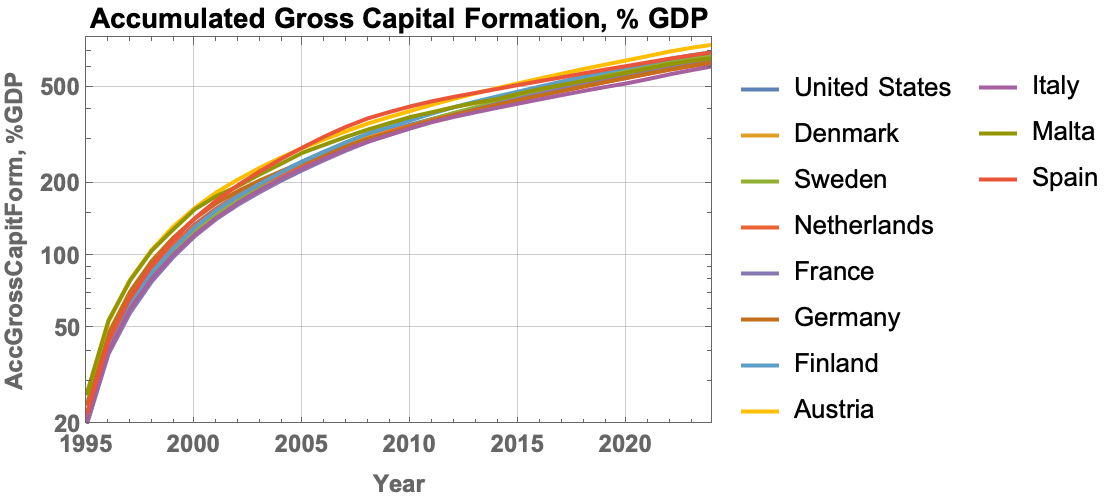

Fig. 4:Foreign trade of Malta and Spain during the analyzed period.A rather unexpected finding is that domestic capital investment follows an almost identical trajectory across countries, regardless of their size or macroeconomic conditions (see Figure 5). Even adding the group of CEE countries would not significantly change the overall picture.

Fig. 5:Accumulated domestic capital investment of countries during the analyzed period.

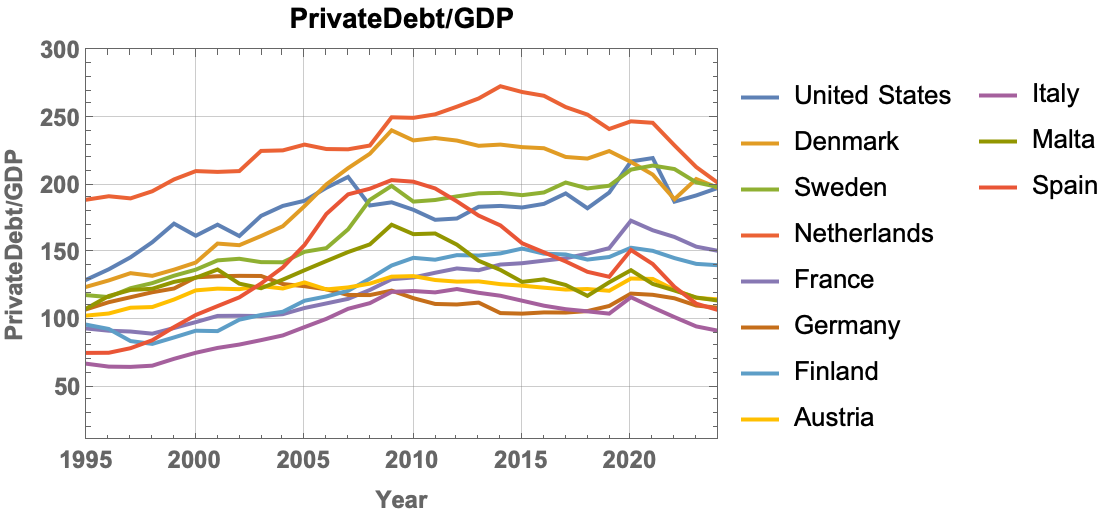

Fig. 5:Accumulated domestic capital investment of countries during the analyzed period.In our earlier study on CEE economies [1], we identified the exceptional role of private debt in cross-country competition. We showed that the rapid growth of Lithuania, Poland, and Romania can be linked to their exceptionally low levels of private debt. Unfortunately, in Western Europe, there are no countries with similarly low private indebtedness; in almost all of them, the level exceeds 100% of GDP, and in some cases, even reaches or surpasses 200% of GDP (see Figure 6)

Fig. 6:Evolution of Private Debt in Western European Countries.

Fig. 6:Evolution of Private Debt in Western European Countries.In terms of private debt, neither Malta nor Spain stands out significantly; however, both belong to the group of countries that managed to reduce private debt levels after the 2008 crisis, while some others allowed it to rise further.

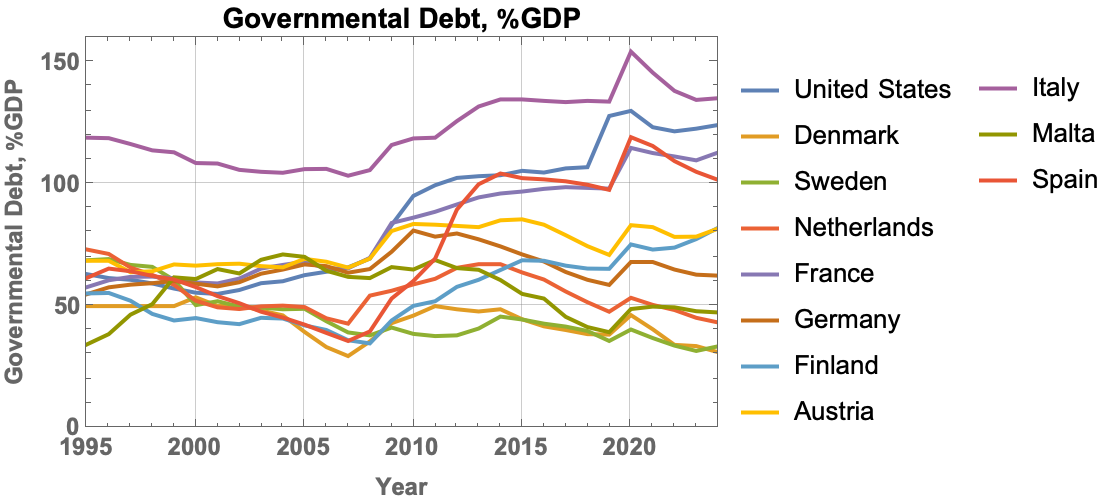

Another key factor in the development of Western and Southern Europe is central government debt. Within this group of countries, the range is from 40% to 150% of GDP (see Figure 7). Our research, along with other studies, suggests that in mature European economies, government debt has a more substantial impact on economic growth than private debt. This contrasts with the CEE region calls for more detailed investigation and explanation.

Fig. 7:Central government debt in Western European countries.

Fig. 7:Central government debt in Western European countries.After the crisis, Malta's government debt fell below 50% of GDP, whereas Spain's (like that of several other countries) rose above 100% of GDP. It is worth noting that all countries that substantially increased their public debt have faced visible economic growth problems—only the United States has been able, at least temporarily, to avoid them.

Key Conclusions

- Malta has demonstrated outstanding economic growth, particularly following significant inflows of foreign direct investment. It is the only country that can clearly be seen as achieving rapid convergence with the United States during the analyzed period.

- Other Western European countries appear stagnant in comparison, though the overall gap with the U.S. remains relatively stable rather than widening.

- The dominant issue across Western economies is rising public and private debt. Despite the United States' even higher debt levels, its growth continues to set the benchmark for the global economy—likely due to the world's reliance on the U.S. dollar.

- Malta's experience demonstrates that, even among developed countries, it is possible to grow faster than its peers. Strong FDI inflows and prudent management of government debt have driven its success.

- Many CEE countries, including Lithuania, have a realistic chance of maintaining similar macroeconomic conditions and continuing to converge toward developed Western levels.

Lithuania, in particular, retains real potential to sustain rapid economic growth similar to Malta's—provided it remains attractive to foreign investment, it keeps both public and private debt at a low level. The greatest challenge ahead is geopolitical instability, as well as the sensitivity of external capital flows to regional tensions.

Note. This text was originally published on gontis.eu. Some changes may have been made to make the content fit Physics of Risk presentation style.

Acknowledgement. This post is based on research conducted by Vygintas Gontis while being affiliated with Institute of Lithuanian Scientific Society as well as with our group (dual affiliation).

References

- L. Kolinets, V. Gontis. Panel regression for the GDP of the Central and Eastern European countries using time-varying coefficients. arXiv:2510.04211 [q-fin.ST].