Price formation from the game theory perspective

Couple of months ago I have started a series of posts on price formation in the free market or how and why the free market does (not) work.

In the first part of the series we have discussed economic laws of supply and demand. We have learned that the cheaper the product is the more people will be willing to buy it. Also that the more people are willing to pay for the product, the more of the product will be produced.

In the second part we have discussed a simple example in which printing press failed to predict the demand for the book. We have discussed how non-optimal prices emerge as a result of this miscalculation.

In the third part of the series we have discussed the implications of the cobweb model, which attempts to explain how the prices and produced quantity converge to equilibrium. We have noted that this convergence is not immediate and may take some time.

Previously we have mentioned that supply and demand laws should be reformulated as areas. As anything above the supply curve is good for the supplier and anything below the demand curve is good for the customer. What we have not yet talked about is why the curves are where they are.

Shifts in supply and demand curves

Standard economic theory states that shifts in the supply and demand curves occur when quantity demanded or supplied changes without a change in price. This could happen for various reasons: changes in taxation, changes in market structure (for example competing products disappear), changes in the supply of raw materials or changes in consumer base. In this post we will briefly discuss the role of competition on the supply curves.

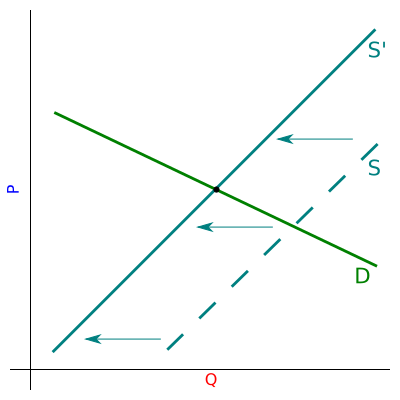

If competition becomes weaker, then the supplier obviously is able to increase the price. Namely the supply law shifts to the left. This shift is somewhat mitigated if the entry to the market is easy and feasible. Then one cannot drastically increase the price as a new competitor might emerge. But the harder it is to enter the market and the easier it is for the existing companies to deter new competitors, the more existing business can increase the prices. As the demand curve shifts to the left (from S to S'), the equilibrium point fill also move to the left and to the right. The new equilibrium will mean that the price will be higher and the demanded quantity of the product will decrease.

Fig. 1:A shift in the supply curve causes equilibrium point to move. Notation is explained in the text.

Fig. 1:A shift in the supply curve causes equilibrium point to move. Notation is explained in the text.Why the competition should keep the prices low?

Imagine that we have two competing companies which produce almost identical competing products. Each of the companies could charge a high price or a low price. If one of them charges low price and the other charges high price, then all of the customers start buying the cheaper alternative. In this case the company charging higher price faces significant losses, while the profits of the other company slightly increase (despite the lower price, they now have more customers).

Now let us assume that we have a market with 100 consumers and 2 suppliers. Those suppliers choose to sell at high (5 monies per unit) or low (3 monies per unit) price. Let us assume that production of 1 unit costs 0.5 monies and that suppliers always produce for all consumers (100 units). Obviously, if suppliers charge the same price, then consumers distribute equally between them, otherwise all consumers choose the supplier selling at lower price.

Hence if both suppliers are selling at high price, then their profits will be: \begin{equation} P_{HH} = 50 \times 5 - 100 \times 0.5 = 200 . \end{equation}

If one is selling at low price and the other at high price, then their profits will be: \begin{equation} P_{L}= 100 \times 3 - 100 \times 0.5 = 250 \end{equation} and \begin{equation} P_{H}= - 100 \times 0.5 = -50 . \end{equation}

If both are selling at low price, then their profits will be: \begin{equation} P_{LL} = 50 \times 3 - 100 \times 0.5 = 100 . \end{equation}

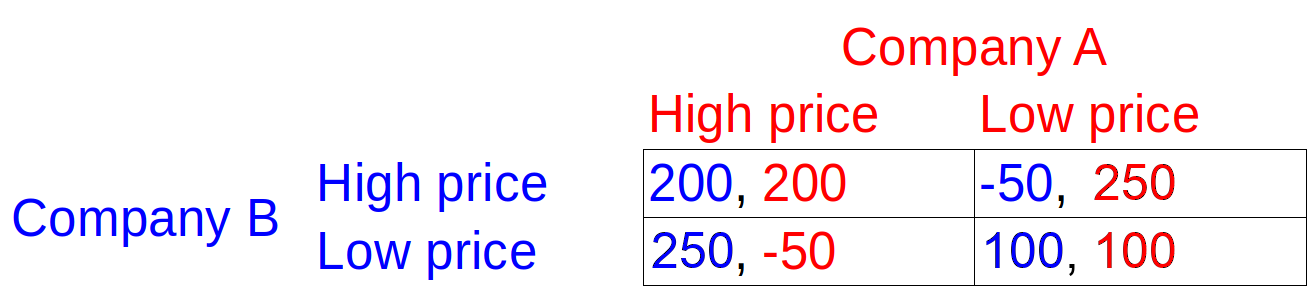

We can formulate this situation as a game known as prisoner's dilemma. See figure below for the payoff matrix of the game.

Fig. 2:A game in which companies A and B decide whether to charge high or low prices.

Fig. 2:A game in which companies A and B decide whether to charge high or low prices.In the figure above we have shown the payoff matrix of the game. Payoffs (profits in this particular case) received by the companies depend both on their choice and on their "opponents" choice. Note that company A is always better off choosing the low price (as the red numbers in the first column are smaller than the respective numbers in the second column). The same is true for the company B as blue numbers in the first row are smaller than the respective numbers in the second row.

Hence the equilibrium (in Nash sense) should be that both companies choose to charge low price. In that case no company can do better by unilaterly changing their action.

How to bypass the equilibrium?

Well, one obvious way is to coordinate pricing. If companies would agree not to betray each other, then they could agree to charge high price. Of course explicit price coordination, cartel deals, is outlawed by the legislators, but it would be perfectly legal under free market extremist views (as they view any regulation as supreme evil).

Another way is to understand that the game is played not once, but infinitely many times (for example, each year or month). In iterated (played over many turns) prisoner's dilemma game this allows for cooperation to evolve. One of the most successful strategies in iterated prisoner's dilemma is called "tit for tat". Using this strategy you tend to cooperate (choose a high price) unless your opponent defected (chose a low price) last turn. In this scenario it is more profitable to always cooperate (choose a high price).

There is also an alternative concept to the Nash equilibrium proposed by V. Sasidevan and S. Sinha [1]. This concept is referred to as "co-action" and is meant to highlight that interacting agents (companies in our case) understand that they both are in the symmetric situation. Hence they both understand that they will act the same and seeing payoff table they are likely to choose cooperation (high price).

Another key point is to note that in order to effectively compete all companies would need to have the resources to be able to satisfy the demand in case the opponent is beaten (goes bankrupt). This is extremely unlikely in practice as it would be extremely risky (high probability of failure and potentially large loss). So if the companies are at least somewhat risk-averse, fierce competition will not ensue.

References

- V. Sasidevan, S. Sinha. Co-action provides rational basis for the evolutionary success of Pavlovian strategies. Scientific Reports 6: 30831 (2016). doi: 10.1038/srep30831. arXiv: 1510.00914 [physics.soc-ph].