Is the United States' productivity advantage merely a result of the chosen measurement methodology?

Global economic media frequently report that U.S. productivity has been growing much faster than in Europe and other developed Western economies for many years. As an example, consider the recent publication in the Financial Times (FT). This is not journalistic exaggeration—such conclusions follow directly from the still widely used methodology of calculating real GDP and productivity, and from international comparisons based on that methodology.

The FT article clearly illustrates that Europe's economic lag behind the United States is treated as an objective reality at the highest levels of politics, and that policymakers have been searching for ways to "close this gap" for many years. We present these remarks because doubts about the magnitude of the United States’ economic advantage naturally arise from the study of international macroeconomics and economic growth theory.

The standard approach

GDP and productivity have long been calculated in constant prices as "real" variables to separate price changes from quantitative increases in production. This is meaningful and partly justified when comparing different periods within the same country. Since our concern is international comparison, we show that the elimination of price growth (as measured by the GDP deflator) is not unambiguous when inflation differs across countries.

International macroeconomics typically uses the following definition of productivity at constant prices:

\begin{equation} \mathrm{Prod}_t=\frac{Y_t^{real}}{PPP_0 L_t} \end{equation}

where \( Y_t^{real} \) is real GDP at constant national prices, \( PPP_0 \) is the purchasing power parity exchange rate calculated in a chosen benchmark year, \( L_t \) is labor input measured as population, employment, or total hours worked.

It is assumed that this measure reflects real productivity changes well. Real GDP removes domestic inflation, while the fixed PPP removes changes in international price levels. However, this choice ignores the interaction among productivity, wages, and prices. The Penn effect—which identifies the relationship between prices and GDP—and its Balassa–Samuelson theoretical explanation appear to be overlooked.

Real GDP does not sufficiently separate output from price changes

It is not difficult to see that changes in currency values and prices affect different components of the economy with very different time lags. For example, wage adjustments occur much later than price changes in internationally traded goods and services. These lags may span several years.

Therefore, changes in real GDP are not independent of exchange rate and price-level changes: later wage increases, triggered by earlier inflation, are reflected in real GDP as increases in the quantity of goods and services produced. Thus, two countries with identical economic capacity in terms of physical production may exhibit different real GDP and productivity values simply because of differing inflation dynamics.

In catching-up economies, wages systematically lag behind prices, yet nominal GDP rises in step with them. Because wages adjust later, this convergence is primarily due to price-level equalization, not an actual increase in physical production. Although this inflation-driven convergence mechanism eventually supports investment, technological upgrading, and genuine productivity growth, measured economic growth is not solely the outcome of internal economic relationships—it is also the result of complex international macroeconomic interactions.

The Penn effect reveals the true dynamics of GDP and productivity

A simplified account of the Penn effect illustrates the impact of international economic interactions:

- Productivity growth in internationally traded sectors raises wages throughout the entire economy.

- Higher wages raise the general price level, including the prices of goods and services traded only domestically. The price levels of less developed countries gradually converge toward those of advanced economies.

A significant part of the measured growth in real productivity is therefore merely the result of international price-level convergence, not an actual increase in production.

Central and Eastern European countries such as Lithuania, Poland, and Romania are converging toward Western Europe partly because of faster price-level growth—not solely due to increased production or improved efficiency. In our view, a similar discrepancy in measured productivity growth exists even across developed Western economies, because membership in different monetary policy regimes leads to divergent price dynamics.

Global economic media often overlook the limitations of constant-PPP GDP measurement and present the United States’ economic advantage over Europe as an indisputable fact. European policymakers likewise reproach themselves as they search for real and imagined causes of this divergence. Mario Draghi's report has fueled endless debate. Because we have serious theoretical doubts about the reported European lag, we provide publicly available comparative results along with methodological commentary.

Comparison of U.S. and European productivity

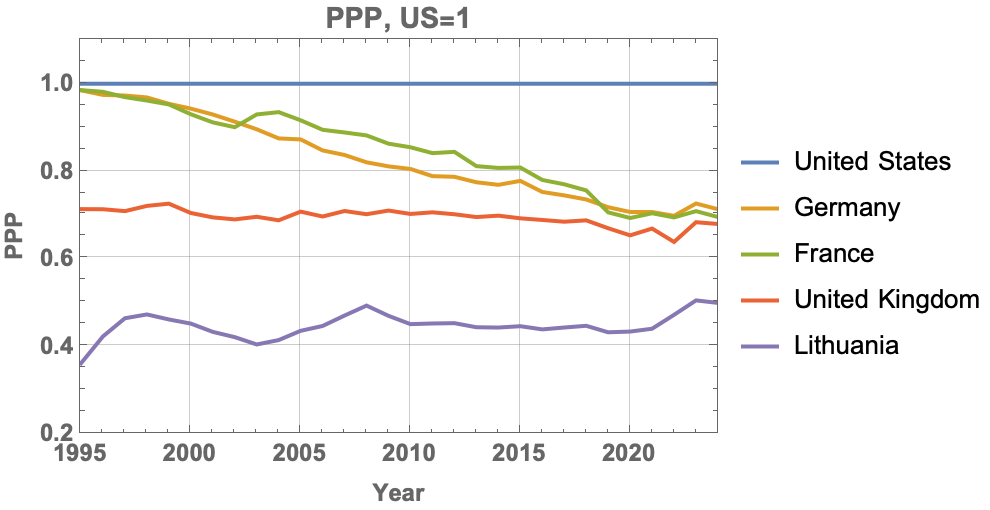

The comparison can be performed using various data sources. We choose OECD data, which is also referenced in the cited FT article. As explained above, differing price-level dynamics may be responsible for differences in measured productivity. Therefore, in Figure 1 we compare PPP changes in the U.S. and European countries.

Fig. 1:Comparison of PPP in the U.S. and European countries. The figure shows how much local currency must be paid in a given country for a good that costs 1 dollar in the United States.

Fig. 1:Comparison of PPP in the U.S. and European countries. The figure shows how much local currency must be paid in a given country for a good that costs 1 dollar in the United States.Between 2002 and 2008, a rapid shift in relative price levels occurred, likely driven by a highly aggressive U.S. monetary policy. This difference has persisted, and the gap between Europe and the U.S. is now even larger than the differences between old and new EU member states. Such a significant increase in the U.S. price level is an essential issue in contemporary global economic relations.

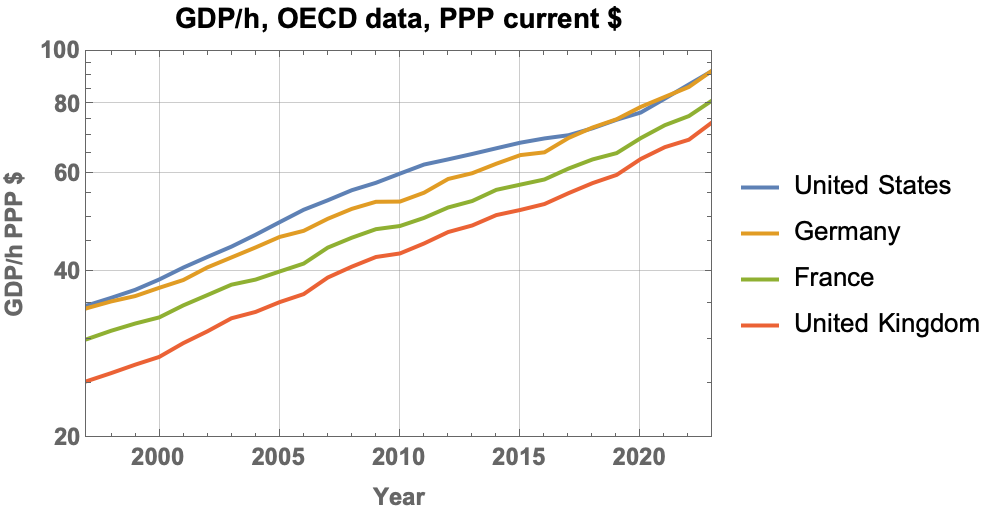

As explained above, it may also contribute to faster measured productivity growth when productivity is calculated in constant prices. Because U.S. wages continue to adjust to higher prices, the formal calculations portray this as an additional increase in productivity. If productivity were measured as GDP per hour worked calculated using current PPP, the U.S. advantage would not look apparent at all (see Figure 2, which shows GDP per hour in current-price PPP dollars).

Fig. 2:Productivity comparison between the U.S. and Europe using PPP with current dollar prices.

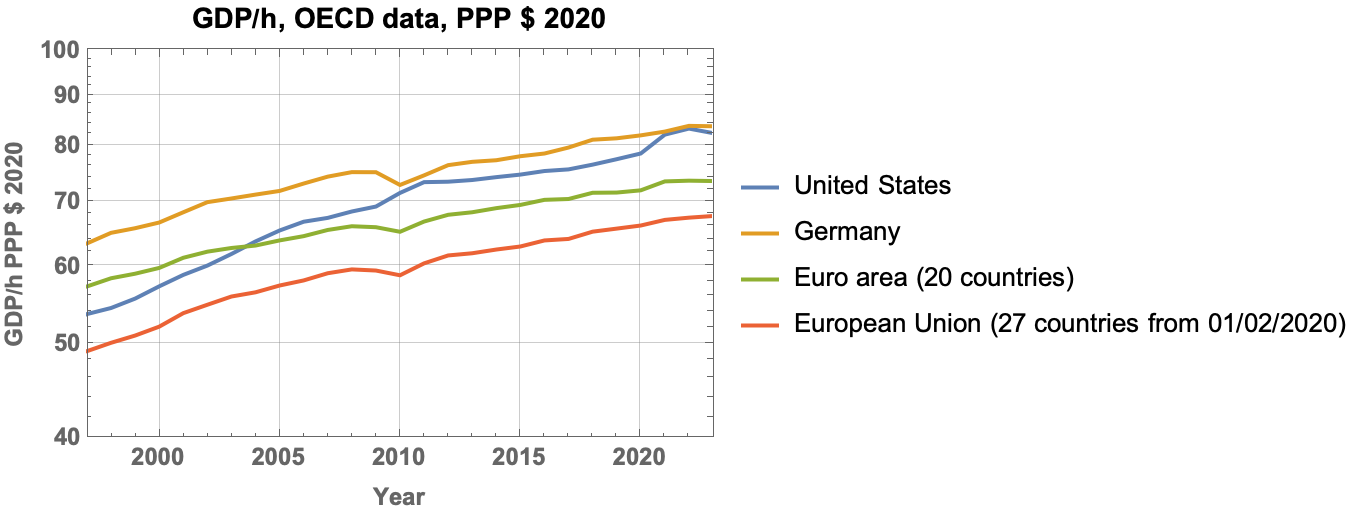

Fig. 2:Productivity comparison between the U.S. and Europe using PPP with current dollar prices.In our view, the faster productivity growth observed in the U.S.—see Figure 3—is a consequence of the long-standing methodological choice to compare countries using GDP growth at constant prices. This approach allows U.S. price increases to be interpreted as real productivity gains.

Fig. 3:Productivity Comparison between the U.S. and Europe Using PPP with a Fixed Price Level (2020 dollars).

Fig. 3:Productivity Comparison between the U.S. and Europe Using PPP with a Fixed Price Level (2020 dollars).One cannot help noticing that when analyzing and comparing economic development across countries, the use of constant-price (real) comparisons often leads to persistent contradictions. Yet despite this, the method remains so deeply rooted that it has become a permanent methodological error in economic literature. This is clearly linked to economic growth theories, whose diversity and abundance do little to resolve these contradictions.

Note. This text was originally published on gontis.eu. Some changes may have been made to make the content fit Physics of Risk presentation style.